The Secret of Aslan

You could see it in their eyes, as they sat there on the bed, silent and still. They were utterly focused, not sure what would happen next, on pins and needles for every detail.

The brilliance of C.S. Lewis, more than fifty years after his death, was still at work. I watched it on display this week in the enthralled faces of twin four-year-old boys, ready to gobble up any piece of information the narrator might disclose about this Aslan.

Longing for the Lion

Four-year-olds can track with more than you might think. At least more than I thought. After watching our sons’ response to another, albeit much simpler, chapter book, we ventured to give Narnia a try. Perhaps it would prove to be too much too soon at their age, I supposed, but I had underestimated Lewis’s brilliance, both captivating and accessible.

So we picked up a copy of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe — don’t believe it when they say it’s “book two” of the Chronicles; Lewis wrote this one first, and Joe Rigney makes a good case for beginning here (Narnian, 163–165).

The Brilliance of the Storyteller

The mention of “Lion” first thing in the title is the placeholder. Chapter 1 introduces the wardrobe; chapter 2, the witch. Surely chapter 3, then, would complete the introductions, but there’s no lion there. Or in chapters 4, 5, or 6. And so the tension grows.

Finally, in chapter 7, the boys caught a sniff, but Lewis was teasing them wonderfully as he describes a beaver in such a way as to make us think that we now may have come across the lion. When the story’s four children realize they are lost in the woods, Susan notices “something moving among the trees over there to the left.”

“Whatever it is,” says Peter, “it’s dodging us. It’s something that doesn’t want to be seen.”

“It’s — it’s a kind of animal,” says Susan. Then follows Lewis’s careful description:

They all saw it this time, a whiskered furry face which had looked out at them from behind a tree. . . . [T]he animal put its paw against its mouth just as humans their fingers on their lips when they are signaling to you to be quiet. Then it disappeared again. The children all stood holding their breath.

The four-year-olds in our house sat in stunned silence wondering if this might finally be the lion. Eventually, Lewis lets us know this isn’t the lion — not yet.

“It’s a beaver,” announces Peter. But the seed has been planted, and is growing.

At the Name of Aslan

Another spell then immediately follows the first. In that first conversation with Beaver, we soon get the first mention of the name Aslan, though we don’t yet know this is the lion. “They say Aslan is on the move — perhaps already landed” — and when Beaver says this,

And now a very curious thing happened. None of the children knew who Aslan was any more than you do; but the moment Beaver had spoken these words everyone felt quite different. Perhaps it has sometimes happened to you in a dream that someone says something which you don’t understand but in the dream it feels as if it had some enormous meaning — either a terrifying one which turns the whole dream into a nightmare or else a lovely meaning too lovely to put into words, which makes the dream so beautiful that you remember it all your life and are always wishing you could get into the dream again. It was like that now. At the name of Aslan each one of the children felt something jump in its inside.

That’s all for chapter 7. Lewis strings us along to chapter 8, when Beaver tells them more about Aslan:

“He’s the King. He’s the Lord of the whole wood, but not often here, you understand. Never in my time or my father’s time. But the word has reached us that he has come back. He is in Narnia at this moment.”

After Beaver recites an old (prophetic) rhyme about Aslan, notching the tension even higher, Lucy asks, “Is — is he a man?” And finally here in chapter 8, almost halfway through the story, we find out that this Aslan is The Lion left hanging from the title:

“Aslan a man!” said Mr. Beaver sternly. “Certainly not. I tell you he is the King of the woods and the son of the great Emperor-beyond-the-Sea. Don’t you know who is the King of Beasts? Aslan is a lion — the Lion, the great Lion.”

Then, of course, Susan and Lucy ask if this lion is safe — to which Beaver answers with his memorable line, “Who said anything about safe? ’Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.”

Catch a Glimpse of His Face

From there, Lewis leaves us dangling as he switches scenes back to Edmund and the Witch in chapter 9. Then in chapter 10, the children meet Father Christmas, but he is not the highpoint of this tale. We’re waiting still with bated breath for Aslan, not Santa.

Next in chapter 11, when the Witch’s servant observes that her winter has thawed, that spring has come, and that “This is Aslan’s doing,” she responds, “If either of you mentions that name again, he shall instantly be killed.”

It’s not till chapter 12 — almost 70% of our way through the book — that the children arrive at the place of the Stone Table, hear the sound of music to their right, and “turning in that direction they saw what they had come to see.” And you could hear a pin drop in our children’s bedroom.

Aslan stood in the center of a crowd of creatures who had grouped themselves round him in the shape of a half-moon. . . .

But as for Aslan himself, the Beavers and the children didn’t know what to do or say when they saw him. People who have not been in Narnia sometimes think that a thing cannot be good and terrible at the same time. If the children had ever thought so, they were cured of it now. For when they tried to look at Aslan’s face they just caught a glimpse of the golden mane and the great, royal, solemn, overwhelming eyes; and then they found they couldn’t look at him and went all trembly. . . .

His voice was deep and rich and somehow took the fidgets out of them. They now felt glad and quiet and it didn’t seem awkward to them to stand and say nothing.

Yes, Like Jesus

Then in chapter 13, when we’ve barely met Aslan at long last, he speaks with the Witch, and then sacrificially gives his life in place of the rebel in chapter 14.

After reading our boys the death of Aslan, we left it there for three days. They accepted the fact that Aslan was dead. When asked to report on the story, they told Grandpa that Aslan had died. (I had to whisper to him that we hadn’t yet read the next chapter.)

This past Saturday night, we opened chapter 15 and read about the “deeper magic,” and turned our mind’s eye with Susan and Lucy to see, “There, shining in the sunrise, larger than they had seen him before, shaking his mane (for it had apparently grown again) stood Aslan himself.” At first, it all seemed too good to be true; and then too good to not be true.

“Aslan’s not dead?” one of our boys asked, to confirm his excitement. “No,” I said with a smile, “he’s alive! He rose again!” The Jesus Storybook Bible had prepared them well for this.

“Like Jesus?”

And so more than fifty years after his death, the brilliance of C.S. Lewis is still captivating new audiences with the glory of Aslan — because Lewis, in all his brilliance, is channeling the glory, not creating it.

Behind the genius of Aslan is the radiance of the glory of God, the exact imprint of his nature (Hebrews 1:3), God’s own image (Colossians 1:15), God’s own fellow (John 1:1). Aslan is too good to not be true — because he is the truth. The secret of Aslan is the glory of Christ.

Whether in fiction or nonfiction, in essay or letter, in apologetics or story, Lewis knew the secret, that the best glory from which to borrow is the beauty of Jesus.

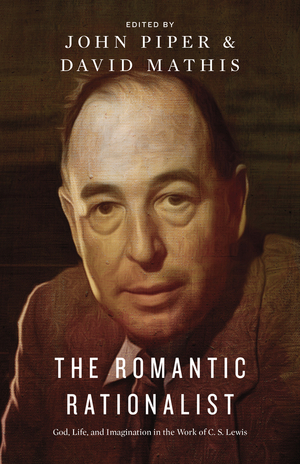

The Romantic Rationalist: God, Life, and Imagination in the Work of C.S. Lewis is now available in paperback, as well as a free PDF.