When Darkness Falls at Christmas

Bethlehem, at the time of Jesus’s birth, was a little town with a population of only about three hundred. Yet within a period of just a few months, it saw the gloriously humble entrance of God the Son into the world, as well as the brutal deaths of baby boys by the command of Herod the Great, who tried to kill the Son. It’s not unlikely that a few inhabitants witnessed both events firsthand.

“When the darkness falls, trust in the Lord’s promises, and not in the way things appear.”

In the fictional scene below, Lemuel, a shepherd who witnessed the angels, visits his brother-in-law Jacob, the innkeeper who had provided the Holy Family the only available place he had at the time. Nine weeks have passed since the Slaughter of the Innocents, where Lemuel suffered the loss of his own boy, Zabdi. Jacob had lost his wife Rachel, his sons, Joseph and Benjamin, and most of his right arm (their story is told in John Piper’s fictional work, The Innkeeper). Both are trying to come to grips with the incomprehensible grace and grief they experienced when caught in the cosmic crossfire that ensued that first Christmas.

“How’s the arm?” asked Lemuel. “Oh, the pain’s getting better every day now,” replied Jacob, holding out the bandaged stump of his right arm. “The strangest thing is that sometimes I can feel my fingers, as if they’re still there.”

Then he squeezed his eyes tight as he choked back a sob. “It’s like that with Rachel and the boys, too.” Both men wept, as they often had over the past two months. When the convulsions of grief passed, Jacob said, “Sometimes I can hear their voices. I find myself looking for them in the next room or out the window.” Lemuel nodded, wiping his nose. “I know. Me too.”

Lemuel had been out in the fields the day the soldiers came. When the sound of women wailing reached his ears, he had come running. But it was too late. He found his wife, Deborah, on her knees outside their door clutching their lifeless son to her breast and rocking in silent agony. Zabdi’s blood covered them both. He was only sixteen months old.

Miriam walked in the room with water for the two friends. “My sister, what a mercy from God!” said Jacob. “She’s kept me alive, and kept the inn in business these nine weeks. Fresh bandages for my arm, cool cloths for my fevered head, hot food for the guests, clean straw for the beasts, and who knows how many trips to the well!” Miriam smiled. “You can’t count that high,” she said, “Can I get you anything?” “I should be asking you that!” said Jacob. “Your time is coming,” she said, leaving with the depleted fruit plate.

“How’s Deborah?” asked Jacob. “That’s hard to say,” said Lemuel, “She’s still not talking much. But I think she’s doing as well as anyone could whose baby and best friend were murdered on the same day. Your Rachel was my sister, but she was much closer to Deborah than to me.”

“And how are you doing?” asked Jacob. Lemuel gently swished his water bowl in circles. “It’s hard to imagine this dark sadness ever lifting,” he said. “It’s like a heavy blanket covering everything.” Jacob nodded and said, “But someday it will. The psalmist says, ‘Light dawns in the darkness for the upright’ (Psalm 112:4).”

This tapped into a deep well of frustration for Lemuel, and he blurted out, “But why did the darkness come in the first place? Four months ago I was so full of joy. The angel flooded us with light when he announced the Messiah had come. And then I saw him, the Messiah — in your stable! We danced together because of this ‘good news’ of ‘peace on earth.’”

“But two months later: darkness. We got violence, not peace. Zabdi and Rachel and Joseph and Benjamin, all killed by that devil, Herod, because he was trying to kill the Messiah. Why? Why would God allow such wonderful light to be swallowed up by such horrible darkness?”

“I don’t know why that evil was allowed,” replied Jacob. “I’m no theologian, but I don’t think God ever answers those kind of ‘why’ questions, at least not in the way we want him to.

“Since Rachel, Joey, and Ben died, Job has become my familiar friend. I’ve thought a lot about Job, about his losses and grief. When his pain raged he asked lots of why questions too, and God didn’t answer any of them. One thing’s clear from Job’s story, though: there was a lot more going on than Job could have understood. And that’s been helping me. How much more true must that be about the Messiah’s coming?

“What happened to our precious ones was evil. It was wrong, just like what happened to Job was wrong. Satan afflicted him and killed his children. I think Satan killed ours too. But God wasn’t out of control when evil struck Job and he wasn’t out of control when evil struck our families.”

Lemuel was quiet for a moment, then said, “So God is in control, but that doesn’t change the fact that your wife and our children are still dead.” “I know,” said Jacob. “And as long as we live we’ll feel the pain of their deaths, and their empty places — like missing limbs that are supposed to be there.

“But the reason this seems so dark to us now is because we don’t yet understand why God allowed it. All the great stories of God’s salvation in the Tanakh contain moments of terrible evil and darkness like this. Part of what makes them great is how God overcomes the darkness with light. His sovereign goodness is so powerful that the worst evil cannot overthrow it, even though sometimes generations pass before God’s victory becomes clear.”

“But it’s so sad that our dead will never know the Messiah’s peace on earth,” said Lemuel, tearing up again. “You don’t know that,” said Jacob, gently. “You and I might not even live to see this peace in our lifetimes. That’s why Job’s hope has to be ours. He believed he would live to see his Redeemer even after he had died (Job 19:25–26). He believed in the Resurrection. That’s our only hope too. The angel said this good news is for all the people, didn’t he (Luke 2:10)? God’s Messiah will overcome all darkness for all his children for all time. All his saints will know the blessing of his peace, Rachel, Joey, Ben, and Zabdi, and everyone who didn’t live to see it come.”

“The thrilling joy of Christmas and the hard realities of life are both beyond our powers to comprehend.”

We too are caught in the cosmic crossfire of Christmas. We experience both “joy that is inexpressible and filled with glory” (1 Peter 1:8), as well as burdens so great we despair of life itself (2 Corinthians 1:8). Both are beyond our powers to comprehend because there is so much more going on in reality than we can yet understand.

When the deep darkness falls and never seems like it will ever lift again, that’s when we must pray for strength to comprehend what is beyond us (Ephesians 3:18), and trust in the Lord’s promises, not the way things appear to us (Proverbs 3:5). For this is what Christmas is all about: “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5).

No matter how dark the current chapter, all our stories in this age will end in everlasting joy in the omnipotent Light that shone first from the little town of Bethlehem.

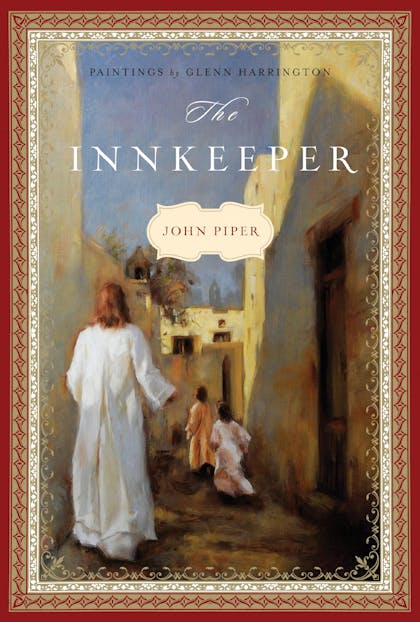

What did it cost to house the Son of God? Through this imaginative poem, John Piper shares a story of what might have been — an innkeeper whose life was forever altered by the arrival of the Son of God.

Ponder the sacrifice that was made that night. Celebrate Christ’s birth and the power of his resurrection. Rejoice in the life and light he brings to all. And encounter the hope his life gives you for today — and for eternity.